The Disease Model of Addiction

If I went to my doctor with a set of symptoms, no one would question the fact that I was sick. No one would impose a moral judgment on me for having those symptoms, and I wouldn’t be viewed as a law breaker for being ill. But many people reject the idea of addiction as a disease and view the chemically dependent person as a social deviant.

Let’s start out by discussing what a disease is. According to Webster’s Dictionary, “disease” is defined as follows:

“Disease: Any departure from health presenting marked symptoms; malady; illness; disorder”

History of the Disease Model:

The World Health Organization acknowledged alcoholism as a serious medical problem in 1951, and the American Medical Association declared alcoholism a treatable illness in 1956. E.M. Jellinek presented a disease model of alcoholism in 1960.

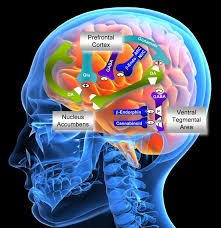

The The Disease Model of Addiction shows the disease in different sources of origin.

Following Jellinek’s work, the American Psychiatric Association began to use the term disease to describe alcoholism in 1965, and the American Medical Association followed in 1966. The disease concept was originally applied to alcoholism and has been generalized to addiction to other drugs as well.

The “disease of addiction” is viewed as a primary disease. That is, it exists in and of itself and is not secondary to some other condition.

Genetics:

Since the introduction of the disease concept, research studies have examined a possible genetic link in alcoholism/addiction. One such study demonstrates that the children of alcoholics are approximately three to five times more likely to develop alcoholism than children of non-alcoholics. However, the genetic influence on other drug addiction has received less research attention.

Another Theory:

In 1983, there was a popular theory of alcohol addiction expressed by D.L. Ohlms in his book “The Disease Concept of Alcoholism” that proposed that alcoholics produced a highly addictive substance called THIQ during the metabolism of alcohol.

Does THIQ Produce Alcoholism/Addiction?

THIQ is normally produced when the body metabolizes heroin and is supposedly not metabolized by non-alcoholics when they drink. According to Ohlms, animal studies have shown that a small amount of THIQ injected into the brains of rats will produce alcoholic rats and that THIQ remains in the brain long after an animal has been injected. Therefore, the theory is that alcoholics are genetically predisposed to produce THIQ in response to alcohol, that the THIQ creates a craving for alcohol, and that the THIQ remains in the brain of the alcoholic long after the use of alcohol is discontinued.

This would provide a physiological explanation for the fact that recovering alcoholics who relapse quickly return to their previous use patterns.

Dopamine and Serotonin Could Play An Important Role:

More recent research on genetic causes of alcoholism has focused on some abnormality in a dopamine receptor gene and deficiencies in the neurotransmitter serotonin or in serotonin receptors.

Biopsychosocial Model:

The symptoms of addiction can develop slowly and unnoticed in the lives of normal people. The biopsychosocial model presents addiction as a brain disease that causes personality problems and social dysfunction. It also allows a clear and accurate distinction to be made between substance use, abuse, and addiction. The progressive symptoms of addiction can be readily identified and organized into progressive stages.

The Naysayers:

Stanton Peele is an outspoken critic of the disease model. On his Addiction Web Site, Ilana Mercer wrote an article declaring that applying the disease model of addiction to chemical dependency is a reflection of an overly permissive society:

“As if embarking on a life of drugs was about one unfortunate glitch. The dangers of gathering more and more behaviors under the disease label is not something about which politicians or health-care specialists care to think, despite the scary ramifications for a society already committed to “morality lite” and to diminished personal responsibility.”

The author of the above quote believes that addiction was declared a disease in order to de-stigmatize it. She asserts that the disease model is medically dishonest, and that a “behavioral problem” cannot be cured with medical intervention.

Lending Legitimacy to the Disease Concept:

How simplistically people impose moral judgments on what they do not understand. And, regardless of how addicts get that way, they still have a set of symptoms, a disease that will ultimately kill them, if left unchecked.

Everyone accepts the legitimacy of chronic conditions such as diabetes and heart disease. Diabetics and people with heart disease look and act the same as non-sufferers of those conditions. We don’t blame diabetics for their illness or find fault with people who have heart disease.

Kevin T. McCauley, M.D. sheds some perspective in an article he wrote for the Texas State Bar Association:

“In making the argument in favor of calling addiction a disease, it is important to tacitly admit that the behavior of addicts is unpleasant. To be sure, the behavior of addicts can be frustrating, revolting even criminal. But in medicine, the character of the patient is separated from his or her symptoms, however unpleasant or harmful. Patients are not judged based on the palatability of their symptoms. If that were the case, patients with cholera would receive the harshest sentences.”

Addicts Have No Control Over Behavior:

I would like to think that physicians do this out of a sense of clinical humility for medicine’s past mistakes. Many times, we have thought we were looking at badness when, in fact, we were looking at a disease process. Just because we observe bad behavior in a patient, we cannot always be certain that what is driving that behavior is some kind of intrinsic badness.

People have a difficult time accepting the validity of the disease model because addiction is ugly, and society looks unfavorably upon that which is cosmetically unattractive. The physical degeneration and self-destructive behavior of a chemically-dependent person cannot be airbrushed away.

The disease model states that addiction is more closely related to an illness over which one has little, if any, control, compared to a behavior that one chooses to enact. Sadly, though, this opinion is not universally shared.

author: Julie Fonda

source: Ground Report