First Nations must find ways to curb alcohol use

Alcohol-related deaths among First Nations in B.C. are a staggering five times higher than for other British Columbians, says a prominent First Nations doctor, who argues aboriginal leaders need to start working on an alcohol strategy to save lives.

Dr. Evan Adams, aboriginal health physician adviser in the office of the Provincial Health Officer, believes First Nations need to get over their discomfort in talking about alcohol misuse.

“It’s hard to bring it up in a safe way without sounding as if you are (buying in) to stereotypes,” Adams said. “It has to be initiated by us – as First Nations – and it needs to happen at every level.”

An alcohol strategy would look at availability of alcohol on reserves, the cost of buying booze and whether it should be increased, education around alcohol misuse and abuse, dangers of binge drinking and the possibility of more reserves banning alcohol.

Under the Indian Act, chief and council, with a majority of voting band members, can pass bylaws prohibiting the possession and sale of intoxicants and prohibit anyone on a reserve from being intoxicated.

In B.C., 17 bands out of 203 have an intoxicant bylaw.

The Provincial Health Officer’s report on the health of aboriginal people, released earlier this year, shows that in 2006, the rate of aboriginal alcohol-related deaths was 15.1 per 10,000, compared to 3.4 per 10,000 for other residents.

Between 2002 and 2006, more than 40 per cent of First Nations deaths in vehicle accidents were alcohol-related, compared to 19 per cent for other B.C. residents.

While there are strategies for dealing with illicit drugs, alcohol is seldom mentioned because it is legal, Adams said. “We forget that alcohol is one of the biggest killers.”

Adams said there’s no evidence of a genetic basis for First Nations alcohol abuse. He believes a more credible explanation lies in social problems such as poverty, stress, overcrowding, unemployment and unhealthy housing.

However, aboriginal societies did not traditionally use alcohol and, until contact with Europeans, most had no alcohol-making abilities. That means communities have had to develop social norms around alcohol use within a few generations, while in other societies, it has taken centuries, Adams said.

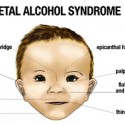

A major concern is binge drinking among young people, he said, adding suicides are more common when young people have been misusing alcohol. Chronic drinking by adults also takes a toll, he said.

“When you have been drinking you do things you would normally never do – sleep around, hit your kids, cut yourself or cry for someone you would never cry for in your right mind.”

Michelle Corfield, who stepped down last month as Nuu-chah-nulth Tribal Council vice-president, said any alcohol strategy would have to look at social issues that cause people to drink.

Corfield, who would like to see intensive alcohol education start in elementary school, said youth binge drinking often leads to victimization of women and young girls.

Andrea Elliott, health manager on the Tsartlip First Nation near Victoria, said alcohol abuse isn’t just a First Nations problem.

“I tend to agree there should be a strategy, but I don’t think there’s much difference between native and non-native cultures,” said Elliott, who wants to see more funding to train counsellors and more efforts to address underlying issues of poverty and overcrowded housing.

“There are going to be people who drink because they need to escape those stresses.”

source: Canwest News Service